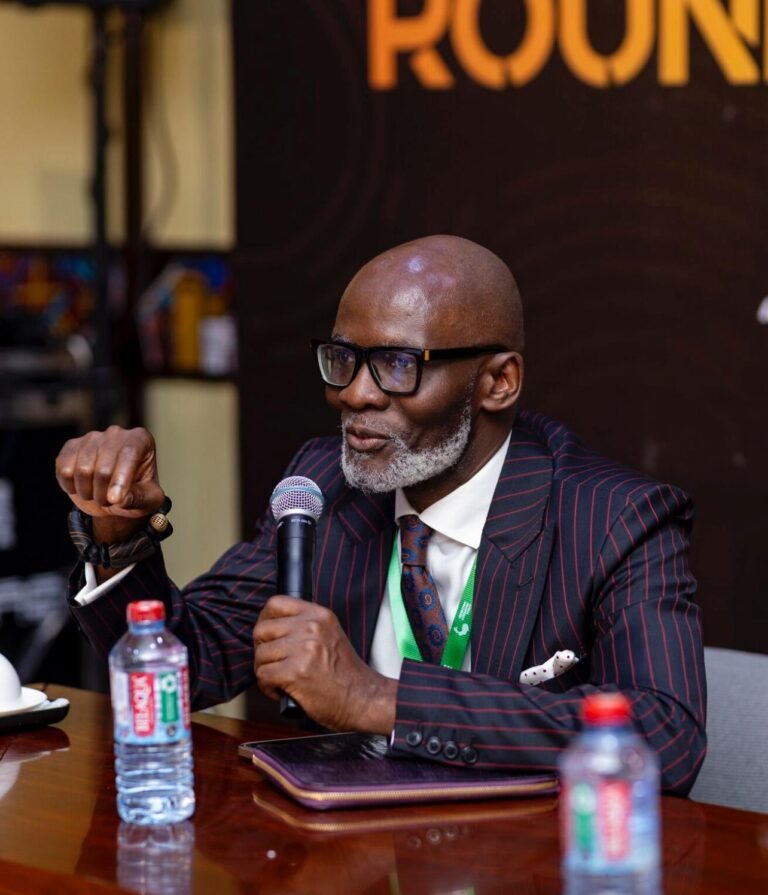

Dr Jeffrey Haynes, Professor Emeritus of Politics, London Metropolitan University, UK

By Professor Jeffrey Haynes

Ghanaians value their democracy. Many express positive sentiments about democracy, including the country’s ‘free and fair’ elections for both president and parliament, constitutionally decreed term-limits, media freedom, parliamentary oversight, executive restraints, and independence of the judiciary.

This information is helpful in assessing the ‘health’ of democracy in Ghana. However, what it does not tell us is how Ghanaians see the relationship of democracy to religion. Should the country be a secular republic – that is, where politics and religion are separate, with no formal political role for the latter – or should Ghana put religion front and central, with a formal political role?

President Mahama appointed a Constitutional Review Committee (CRC), chaired by Professor H. Kwasi Prempeh, in January to gauge the opinions of stakeholders in governance. The eight-member committee was tasked with identifying gaps and challenges in the implementation of previous constitutional review efforts. This was timely, given that democracy is under attack in many parts of the world, including in several of Ghana’s neighbouring countries, and when there is pronounced scepticism in Ghana itself about the quality of the country’s democracy.

CRC met with religious leaders at the Alisa Hotel, Accra, on 15 September. Much of the meeting is said to have been concerned with whether Ghana is ‘secular’ or ‘religious’. According to one of the participants, religious leaders showed their misunderstanding about what the former mean, believing that ‘secular’ means ‘atheist’.

Christian leaders identify Ghana as a ‘Christian’ country, claiming that as the country is 71.3% Christian according to the latest census in 2021, then Christianity should be privileged over minority faiths. Affirming Ghana as a ‘Christian’ nation – as was done in Zambia in the mid-1990s – might however undermine the current constitutional position: the state is secular, and all religions have constitutional equality.

The Christian Council of Ghana raised various issues with President Mahama during a meeting on 18 November. Some were squarely political issues, including the fight against illegal mining (galamsey), the stalled Anti-LGBTQ+ Bill, the fight against corruption, and youth unemployment.

Representatives of the Christian Council also raised the controversial issue of the stalled national cathedral. They urged President Mahama to take decisive action to resolve this issue, because, they asserted, it is central to the country’s socio-economic well-being – allegedly it would bring in hundreds of thousands of foreign tourists who would spend millions of dollars and bolster the economy – and because many Ghanaians are said to be concerned about the project.

The president explained that the government is awaiting the outcome of a ‘forensic audit into the project’s accounts after an initial audit commissioned by the Board of Trustees revealed issues’. While expressing his personal support for a Christian ‘interdenominational place of worship’, President Mahama stated that he was not convinced that it is necessary or desirable to spend up to $400 million on the project. He promised consultation with the Christian community on how to proceed.

Critics have noted the difficulty of reconciling two apparently conflicting positions: on the one hand, the Christian Council is requesting President Mahama to continue building the so-called National Cathedral presumably with contributions from the tax payer while, on the other hand, millions of Ghanaians continue to experience poverty and a lack of development. Some have called into question Mr Mahama’s judgement that despite continuing economic hardships experienced by many Ghanaians, after the audit on the cathedral is finished, he is willing to sit down with the church representatives to discuss how to build a fitting place of worship. Some might see this as insensitivity to Ghana’s economic plight.

The saga of the national cathedral is not only about government priorities. It is also at the heart of the question whether Ghana is secular or religious: is the country a ‘Christian’ nation? It might be argued that it is not the job of Ghana’s government to build a place of worship for any of the country’s religious traditions, including the majority faith, Christianity. The people of Ghana did not elect President Mahama to guild a national cathedral for Christians. As many have pointed out, if Ghana’s Christians want a national cathedral, then the church should finance its construction from voluntary contributions from its members.

If not to build a national cathedral, why did the people of Ghana vote overwhelmingly for Mr Mahama and the National Democratic Congress in last December’s general election? Ghanaians voted for them to deal with crucial ‘bread and butter’ issues, including illegal mining (galamsey) and associated environmental devastation, high level egregious corruption, and the scandal of fast-growing youth unemployment. Put another way, Ghanaians voted for Mr Mahama and the NDC in the expectation of fast and positive change to resolve the concrete problems that many have to endure every day.

The Constitutional Review Committee was due to submit its report to the president last Monday, 24 November. Over the previous 10 months, the Committee robustly engaged with stakeholders to gather diverse perspectives and formulate actionable recommendations to strengthen Ghana’s democratic processes. Government sources say President Mahama has expressed strong interest in the committee’s findings, for further action. It will be interesting to see if the Committee makes recommendations about the constitutional place of religion in Ghana and if it does what President Mahama will do in response.

The writer is an Emeritus Professor of Politics at London Metropolitan University, UK.